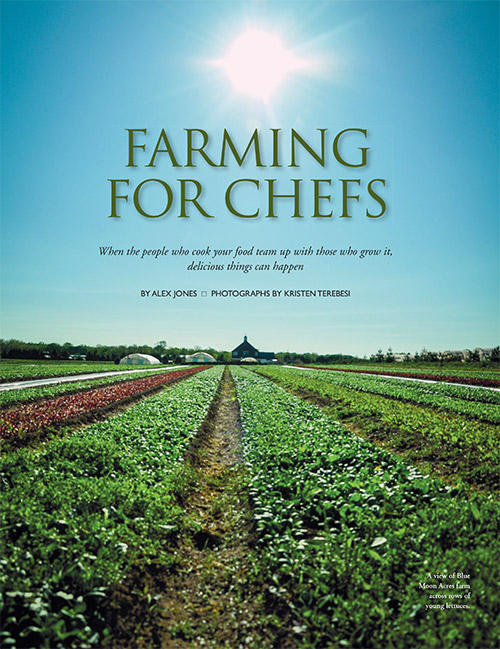

Blue Moon Acres Featured in Edible Philly Magazine: Farming For Chefs

Many of us are old enough to remember the days before recycling bins, when bottles, cans, and plastic all went into the trash, no questions asked. As a nation, we’ve come a long way since then—over 87 percent of us currently have access to curbside recycling programs—but much work remains to be done. In fact, while 75% of American waste is recyclable, only about 30% actually is.

Many of us are old enough to remember the days before recycling bins, when bottles, cans, and plastic all went into the trash, no questions asked. As a nation, we’ve come a long way since then—over 87 percent of us currently have access to curbside recycling programs—but much work remains to be done. In fact, while 75% of American waste is recyclable, only about 30% actually is.

As a practice, recycling is an incredibly important action, one that saves not only raw material, but energy as well. Recycling one aluminum can saves enough energy to listen to a full album on your iPod; recycling 100 cans could light your bedroom for two whole weeks! Recycling also keeps material out of landfills, and in general encourages an awareness of ones’ waste. And yet, America lags behind most of the developed world when it comes to total volume recycled.

In Belgium and Sweden, 1 percent of total trash ends up in landfills, compared with 69 percent here in the United States. And in the Netherlands and Germany, 62 percent of trash is recycled or composted, and the other 38 percent is turned into energy from waste (EfW). Stricter European laws around recycling and waste are the main reason for this. Here in the States, only 7 percent of trash ends up recycled.

A recent HUNblog article sums it up nicely:

“In most European countries, glass and paper are just some of the things the average European refuses to throw away. At most supermarkets, beaches, and other public places there are bottle banks with separate slots for clear, green, and brown glass. Europeans also recycle hard and soft plastics, as well as newspaper and cardboard. Most towns in countries throughout Europe have a free paper collection once a month and most people recycle everything made of cardboard or paper, from cereal boxes to old telephone bills. In addition, there are recycling plants or recycling centers all throughout Europe which totally facilitates and promotes their recycling effort. Green waste, such as garden trimmings, is up out on the street in a neat bundle and they are collected every two weeks. If that’s not enough, aluminum and tin cans be taken to local depots, old batteries taken to the local supermarket, and old oil or other chemicals taken to special sites.”

America’s program could be just as ambitious, but change must be centralized. Writes Matt Kasper of the Center for American Progress, “In order for the United States to begin reducing the amount of waste sent to landfills, increasing recycling rates, and generating renewable energy, a municipal-solid-waste portfolio standard must be enacted by Congress and applied nationwide in order to decrease greenhouse-gas emissions from landfills, and individual states should include EfW in current renewable-energy portfolio standards.”

America’s program could be just as ambitious, but change must be centralized. Writes Matt Kasper of the Center for American Progress, “In order for the United States to begin reducing the amount of waste sent to landfills, increasing recycling rates, and generating renewable energy, a municipal-solid-waste portfolio standard must be enacted by Congress and applied nationwide in order to decrease greenhouse-gas emissions from landfills, and individual states should include EfW in current renewable-energy portfolio standards.”

A very good start, to say the least.

Everybody loves a freshly-cut Christmas tree. The smell, the look, the feel of all that winter greenery, right there in your home. But just what all goes into creating that tree? Christmas tree farming seems like it would be easy, but it’s actually quite time-intensive and laborious.

Everybody loves a freshly-cut Christmas tree. The smell, the look, the feel of all that winter greenery, right there in your home. But just what all goes into creating that tree? Christmas tree farming seems like it would be easy, but it’s actually quite time-intensive and laborious.

Each Christmas season, between 35 and 40 million trees are sold in the United States alone. An average tree farmer plants around 2,000 trees, of which only 750 to 1500 survive to harvest. It takes an average of 6 to 10 years for a tree to reach maturity. Each tree costs around $5 to $10 from the time it’s planted until the time it’s harvested. Being a Christmas tree farmer can be profitable, but is not without risk.

Planning for the Christmas season begins in earnest in July, but farmers spend 11 months of each year tending to their crop, only really resting, ironically, in December, when all that’s left to do is sell. Spring and summer are particularly busy: farmers spend long hours controlling competition from other plants. Insects and disease can also cause serious damage; farmers often have to quarantine individual trees to save the crop.

Pests can also be problematic: if the fields are left unmowed and unweeded, rodent populations swell, and entire strands of trees can be destroyed.

In non-organic tree farms, trees sometimes need to be treated with herbicides or pesticides, to help control diseases and predation. In organic farms, however, chemicals are not used, requiring more mowing and pruning.

So next time you meet a Christmas tree farmer: give him/her a hug and thank them. It’s hard work!

India’s small farmers are in trouble. A perfect storm of climate change, globalization, and government ineptitude is battering away at what was once the country’s most common occupation. The last two decades have seen an explosion in farmer suicides, as indebtedness, crop failure, and usury leave them hopeless and desperate.

India’s small farmers are in trouble. A perfect storm of climate change, globalization, and government ineptitude is battering away at what was once the country’s most common occupation. The last two decades have seen an explosion in farmer suicides, as indebtedness, crop failure, and usury leave them hopeless and desperate.

The crisis began in 1991, when economic ‘reforms’, exposed Indian farmers to global competition; specifically to the US and UK who receive huge government subsidies. These subsidies drive down prices, resulting in diminished profits and, in some cases, product having to be sold at a loss. Without similar subsidies of their own, the small Indian farmer remains effectively barred from the market.

Those who do remain have to turn to high-cost seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides in order to compete. However, because small farmers in India cannot qualify for bank loans, they are forced to borrow from loan sharks who charge interest rates in excess of 20%. These loan sharks frequently raise rates, so that 40% and even 50% interest is not uncommon. Along with the effects of globalization, it is this ever worsening cycle of indebtedness that has led to an alarming number of farmer suicides.

Since 1995, 270,000 farmers have committed suicide. In 2014, 5,650 farmers killed themselves, roughly 4.3% of all farmer suicides. That’s one farmer every 41 minutes. Of these, 21% were directly related to bankruptcy or indebtedness.

Of course, the effects of climate change are not making the situation any easier. Extreme weather events, drought, and heat waves have proven a deadly combination. The drought of 2002, the heat wave in May 2003, the extremely cold winters of 2002 and 2003, the flooding of 2005, and the 23 percent rainfall decline in the 2009 monsoon season—these are just some of the extreme weather events that have taken a heavy toll on crop output.

Other than reversing globalization, the best way to help India’s small farmers is to provide them access to modern farming technologies and methods: biological pest control, mechanical cultivation, crop rotation, and use of green manures and composts. Additionally, the government needs to educate farmers about the various funding and assistance available to them, as well as implement skill-development programs. The government would also do well to develop improved rainwater-harvesting methods, diverting water from perennial rivers. Groups like Save Indian Famers are doing what they can to help widows of deceased farmers, and to help families escape from mounting debt.

Other than reversing globalization, the best way to help India’s small farmers is to provide them access to modern farming technologies and methods: biological pest control, mechanical cultivation, crop rotation, and use of green manures and composts. Additionally, the government needs to educate farmers about the various funding and assistance available to them, as well as implement skill-development programs. The government would also do well to develop improved rainwater-harvesting methods, diverting water from perennial rivers. Groups like Save Indian Famers are doing what they can to help widows of deceased farmers, and to help families escape from mounting debt.

The plight of the Indian farmer, though distant, is not so different from our own. As small farmers, we would do well to work against the same forces that are driving so many to despair so many miles away.